What do these stories have in common?

A 21st-century ark blasts into space with a crew of teens who must abandon Earth to avoid a mysterious epidemic and preserve the future of humankind.

A weary and nameless father and son trudge the ashen landscape of what appears to be a post-nuclear war America.

Finally, a plague of zombies terrorize late eighteenth century England.

End-of-the-world fervor

Three books have sat on my desk far too long, all begging to be returned to the library for other borrowers. They are Dom Testa’s young adult novel The Comet’s Curse, Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize winner The Road, and Seth Grahame-Smith’s clever bit of literary piracy Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.

Mixing the three in one article may seem unfair or ungainly, yet together they provide a picture of the current rage for end-of–the-world tales.

This is particularly exemplied by a Hollywood’s current apocalyptic fit ranging from the hilarious Zombieland to the special effects blockbuster 2012 to the grim and grimy movie based on McCarthy’s novel.

Plus, it appears that a television mini-series is planned for Pride and Prejudice and Zombies and that Testa’s novel—book 1 in his Galahad outer space series—has also been optioned. It is easy to imagine a teen television series based on the Galahad stories.

Millenialism in the 1800s and beyond

Apocalypse has a way of popping up during tough times. John H. Martin’s book Saints, Sinners, and Reformers provides useful perspective on this phenomenon in the chapter “The End of Time and the Adventists.”

This particular chapter concerns the Christian idea of “millennialism” in which Christ returns to earth, the saved rise to heaven, and the sinners sink into hell.

From the late 1830s through the 1840s, Martin notes, the “white heat” of millennialism consumed much of America partly due to the “widespread economic distress after the 1837 economic panic in the United States, and this seemed to indicate that the world was growing more hopeless. Millenialism has always flourished in difficult times….”

This brings to mind the feverish popularity of Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins fundamentalist Christian Left Behind series just a few years ago. As the “saved” abruptly leave the everyday world to ascend to heaven, car crashes and all sorts of bedlam occur.

Tough times inspire end-of-time fiction

Although the first Left Behind book was published in 1995, the series really took off in the years following the September 2001 destruction of New York’s Twin Towers and as our nation began facing a slew of corporate financial disasters such as the Enron bankruptcy scandal.

Tough times have simply become tougher in the past two years what with the Iraq and Afghanistan wars still unresolved, the AIDS epidemic still unchecked in Africa, and the economy still limping.

Remember when you were a teenager and an outbreak of acne got your mind off all other problems? For a nation weary of belt-tightening and soldiers coming home in body bags, perhaps end-of-the-world novels and movies are a welcome distraction.

Here are three views of the end of time as posed in the novels mentioned at the beginning of this article.

Teens in space: The Comet’s Curse

Where does this author get all his energy? Dom Testa is a morning drive-time radio personality on Denver’s lively “Dom and Jane Show.”

The Comet’s Curse, A Galahad Book, by Dom Testa

Tor Books, 2010

ISBN 0-765-32107-6

Testa is also the author of six YA novels in the Galahad series about super competent teenagers who are chosen to save humankind from extinction by voyaging into outer space when Earth becomes tainted with a deathly virus.

As the young crew of spaceship Galahad departs Earth, they leave their families behind forever. While this is deeply sad if one takes time to ponder it, the characters in Comet’s Curse are far too busy doing their jobs and solving a dangerous mystery to let grief overwhelm them.

Plus, Testa, who is naturally lighthearted on air as well as in his writing, has created a wise-cracking central computer called Roc not only to help the crew run the ship but also to cheer them up.

Roc is as reflective as it is witty:

I used to live in a box…. And not a very big box either. Just a small, metal container with patch bays, microchips and a mother of a motherboard….

Although Roc is in no way humble and thinks of itself as a “masterpiece,” it sums up its beginning as being a boring “string of ones and zeroes, a few equations, a bazillion lines of code….”

Roc is glad to be out of the box and into its “new digs” aboard the circuitry of Galahad. “I like the crew I’m sailing with. I like the challenge.”

I like Roc and I like this book. It helps teens to contemplate the time when they will part from childhood and head into the scary reaches of adulthood.

Paternal love prevails: The Road

The two main characters have no names in The Road. As the novel opens, the father and son are simply identified as “he” and “the child.”

The Road, by Cormac McCarthy

Vintage, 2009 Movie Edition

ISBN 0-307-45529-7

Their daily lives are a grim progression from one frigid hideout in an ashen landscape to another as they try to avoid roving bandits, some of whom it appears have sunk to cannibalism.

Humankind seems to be in its last, brutal days. What caused this downfall is unclear and unimportant. One way or another, the world has gone mad.

Cormac McCarthy’s language is spare yet hauntingly beautiful as in this scene where father and son begin their day’s journey.

He shifted the pack higher on his shoulders and looked out over the wasted country. The road was empty. Below in the little valley the still gray serpentine of a river. Motionless and precise. Along the shore a burden of dead reeds. Are you okay? he said. The boy nodded. Theyn they set out along the blacktop in the gunmetal light, shuffling through the ash, each the other’s world entire.

There is poetic economy in the phrase “each the other’s world entire.” It can also be seen as a summation of the entire novel, which turns on the intense bond of father-child love. Where there is love, there is hope for a better tomorrow.

While some have found this new world too harsh to bear and have escaped through suicide, the father cannot give up on the idea that his son will have a future. He refuses to give in to the fear of danger, cold, and near starvation, even maintaining a soothing ritual of bedtime read-alouds for his son.

Some may find it difficult to persist in reading the entire novel, eventually skipping ahead to learn the outcome for father and son. That is how it was for me when I first encountered the novel during a disturbing time in my own life.

When you are in desperate need of cheering up, this is hardly the novel to provide it.

Trailers for the movie version of The Road are, of course, bleak. It is impossible not to wonder why anyone would want to see it at holidays, especially since it doesn’t appear to have the saving grace of the author’s poetic voice.

Although The Road is an important book and lyrically written, it is depressing enough to make a reader seek the somewhat jollier company of zombies.

The plague: Pride & Prejudice & Zombies

This series of articles began with zombies and will end with zombies. Why are they the monster of the moment, popping up in teen and adult novels, political commentary, blockbuster movies, and gaming software?

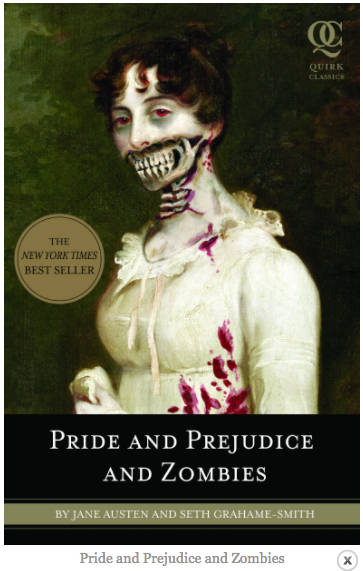

Pride an Prejudice and Zombies, by Seth Grahame Smith and Jane Austen

Quirk Books, 2009

ISBN 1-594-74334-7

Perhaps they are the perfect punching bag for the woes of our time. While there may be a rare author who has managed somehow to create a zombie romance, there appears to be nothing appealing about these brain-chomping undead ghouls except as objects to bash and overcome.

Yet zombies seem to be able to make people laugh, especially in movies such as Zombieland, at a time when we very much need it.

Seth Grahame-Smith’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies has its giggles.

It is amusing to read how Elizabeth “Lizzie” Bennet and her sisters trained with a martial arts master in China in order to become efficient zombie fighters. In fact, it is Lizzie’s great fighting skill that her nemesis and eventual paramour, Mr. Darcy, finds so attractive.

Remember the scene where the pushy, empty-headed Mrs. Bennet is delighted, because her husband has befriended the wealthy bachelor Mr. Bingley? In Grahame-Smith’s version, Mr. Bennet warns his wife that the girls may attend a ball, but must “continue their training.”

‘Of course, of course!’ cried Mrs. Bennet. ‘They shall be as deadly as they are fetching!’

Grahame-Smith is a good mimic. He makes all the zombie talk sound like Jane Austen’s characters might actually say it. For example, the undead monsters are referred to as the “unmentionables,” the “dreadfuls,” and the “sorry stricken.”

The author provides other funny twists such as when Lizzy discovers that her best friend, Charlotte, has only agreed to marry Lizzy’s portly, priggish cousin, the Rev. Collins, because she has been infected by a zombie bite.

Collins is so self-centered that he doesn’t notice as his new wife gradually begins to drool, rot, and slur her speech. It can’t be long, the reader thinks, before Charlotte will be cracking open his head to get at his brains and shut him up.

Since the original Pride and Prejudice has long been out of copyright, Grahame-Smith was able to use 85 percent of Austen’s text verbatim, supplementing it at strategic points with his zombie story line.

But Pride and Prejudice and Zombies grows tiresome. Readers may find themselves enjoying Austen’s writing versus Grahame-Smith’s additions. Some things just can’t be improved upon.

Goodbye to the sorry stricken

While it is fascinating to ponder why there is so much apocalypse filling library shelves and movie theaters these days, enough is enough. I think we are all ready for days of grace, but perhaps that will take a head adjustment. We need to find reasons to smile and create our own respite from the daily dread of worrying about how to pay the bills, afford healthcare, and bring our soldiers home.

For some, that may mean tales of vampires, werewolves, zombies, and the end of the world. For me? It’s time to move on to a different part of the library.

Alicia Rudnicki©, originally published at Examiner.com, 2010